Fear or curiosity? Hesitance or excitement? Depression or hope? What do you feel when you face something unknown to you? This was the first question I asked my self the moment I learned I’m going to talk about “Embracing the Unknown” at the Liechtenstein-based Think- and Action-Tank THE HUS Institute, which eventually evolved to this article.

The theme of the morning was announced “Know Thyself,” by The Hus Institute and I was going to argue that “embracing the unknown” will provide a mindset that not only leads to unknowing ourselves but also gives us the chance to build/rebuild ourselves.

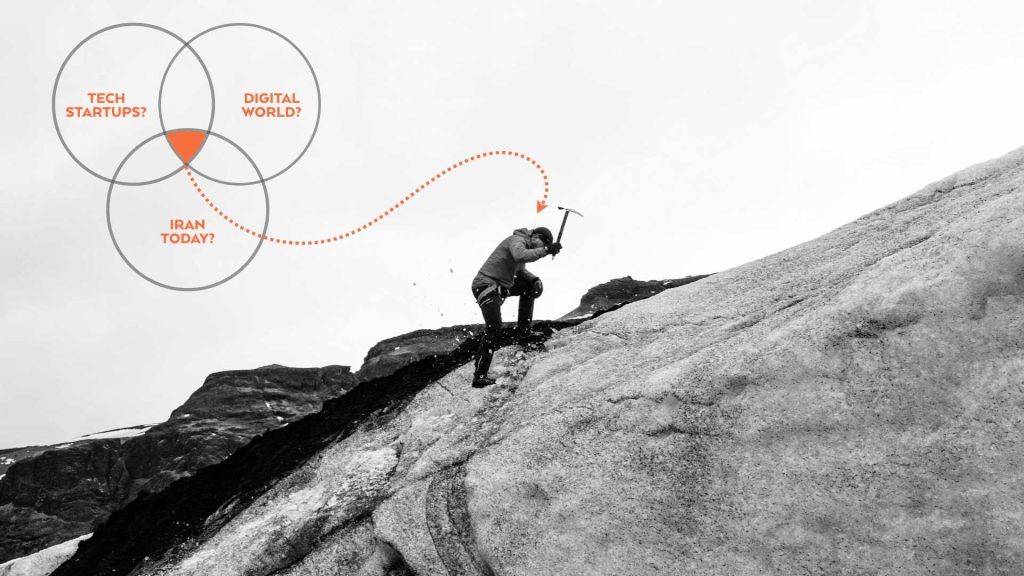

Dedicating my carrier to help innovation and startup culture grow in Iran, I found myself working and living in the middle of three uncertain and unknown areas, where I believe also offers a world of opportunities. On a daily basis, I have to deal with the uncertainty of the modern digital world, combined with the unknown cloud of startup works and chaotic trends of Iran’s economy. “Radical Openness” as The HUS Institute Co-Founder and German Futurist Christopher Peterka puts it, is what in my experience converts unknown to opportunities. But what is unknown and sophisticated about the world? Startups? And Iran?

The World Upgraded To A More Complex Version – Discussion at The HUS Institute

The first growing unknown area for me is how the world become during the past 40 years. It’s getting more and more complex.

Back in the ’80s, when I was a kid, there was no such thing as a personal computer. To share a photo with your loved ones, you had to use film to take pictures, got them developed in photoshop (not the software), and mail copies to your relatives. Roughly half of the 4.4 billion people on Earth were either so poor that they were cut off from the rest of humanity, or lived in regimes so repressive that no outside communication was possible. AT&T was the only telephone operator in the United States; telephony was just one of many high-impact industries that were highly regulated and protected from competition.

Today’s decision-makers face environments in which things that were isolated from one another just 30 years ago are bumping up against each other, often with unexpected results. That’s because of a host of technological and sociological changes that occurred after 1980:

- Digitization of massive amounts of information,

- Smart systems that communicate interdependently,

- The decreasing cost of computing power,

- The increasing ease of communicating rich content across distances,

- The rewriting of industry norms and business models

For instance, it used to be possible for organizations to control what information escaped their four walls. Today, customers can connect on social media sites; employees can tell the world what it’s like to work somewhere, and businesses are routinely evaluated on sites such as Yelp and TripAdvisor. Managing your reputation and its attendant risks has become far more complex.

Citizens also used to assume some privacy in how they engaged with government and take advantage of their connections; that, too, is more complex and less clear today. During the past few months, there was a massive devaluation of Iran’s Rial in comparison to international currencies. For that reason, the government of Iran guaranteed to subsidies what is called “the essential goods” like wheat. Like a handful of other countries, of course, some people used their ties to the government to use this subsidy benefit and import luxurious cars like Maseratis to the country as “the essential goods.”

Ministries started to publish a list of people and organizations who had the clearance to use these subsidies to import goods. Some social media channels mashed this publicly available information together with address records and digital maps. This sort of thing challenges legal procedures, public safety, and how we conduct our political process in ways that would have been unimaginable in 1980.

The Happy Cool Startup People

The second unknown area that I’m dealing with is the world of startups. What is this disruptive innovation that entrepreneurs always seek for? It’s by definition seeking activities where there isn’t proof that we are on the right track. When you google the word “startup”, you see so many photos like toothpaste commercials, everyone laughing and having a good time on bean bags!

But, in my experience, entrepreneurship is anything but cool. It is, at times humiliating, painful, and embarrassing. We make so many mistakes: we scale too early, we scale too late, we talk to too many customers, we speak to wrong customers.

We are trying to do

“Risk” is like playing poker. Understanding the odds gives you a competitive advantage. When rolling dice, there are only so many options — and you can analyze everything. That is the nature of risk — it is knowable, it is quantifiable. Incredible wealth has been built upon taking risks. If you have short time horizons, a 51% chance of winning and make small bets, you can’t lose.

But transformational businesses are not built that way. There are three ways to make money:

- capture an existing piece of the market

- expand the market

- create an entirely new market

In venture we look for 10, 20, 100, 1000x returns… As such, only truly transformational businesses can return the portfolio. This means that only expanding the market and creating an entirely new market are interesting for us. The best businesses build value where previously there were no competition, no comparable costs. Uber, Airbnb, SpaceX, Tesla, ESPN — all these companies defined an industry, creating something from nothing. That is where the money is made.

This isn’t risk, however. Yes, it is risky, but not risk. Initial investors of Uber or Airbnb’s didn’t do odds of success, because there was no formula. All estimates were assumptions, with every investor and entrepreneur interpreting the risk differently. The best things in life aren’t risky; they are unknowable. That uncertainty is the difference between a 10x and a 10,000x investment, and in my experience, greatness happens when investors are uncertain, and founders are 100% certain.

The Infinite Game Of Iran’s Economy

The third unknown area of my job is where it happens: Iran. A country and an economy so chaotic that’s by nature is a paradoxical dilemma. Iran is a country of 80 million where there are so many ethnicities. It has occupied 1% of the world’s surface and is enriched with 8% of the world’s natural resources, not to mention it’s tremendous human capital potential. The country has the 4th rank in the world in terms of the number of engineers, and about 65% of its population is under 35 years old. It’s experiencing a roller coaster of ever-changing economic and geopolitical.

There tons and tons of articles on how and why do business with Iran along with a handful of analyses. I also have done my share by writing 7 Things You Need to Know Before Doing Business in IRAN last year. The root of all these uncertainties is unknown, yet it seems to be highly relevant to Iran’s sanctions. After Iran’s revolution in 1978, for almost 40 years, Iran has been under various economic sanctions. They were never indeed lifted, but

In 2016, then-US presidency candidate Trump frequently criticized the JCPOA, at one point panning the agreement as “the worst deal ever negotiated,” and threatened to withdraw the United States from the JCPOA if its terms were not renegotiated. Following his election, Trump reluctantly certified Iran’s compliance with the nuclear deal twice, on May 2017 and July 2017.

On May 8, Trump formally announced the United States withdrawal from the JCPOA and signed a presidential memorandum to “begin reinstating nuclear sanctions” that were lifted pursuant to the JCPOA. President Trump also intimated that further, new sanctions were possible, asserting that the United States “will be instituting the highest level of economic sanction” and that “any nation that helps Iran in its quest for nuclear weapons could also be strongly sanctioned by the United States.”

All this brought the country a lot of economic uncertainty. The Iranian Rial devaluated to almost 60%, and business owners are so uncertain that they don’t know the price of the products they are selling. For instance, when I wanted to renew my MacBook, I went to a local store and asked for a price. The shopkeeper had to make at least ten calls to give me the price for the day because the price for the same product might have been different the day after.

So I asked at The Hus Institute, how do we (as entrepreneurs) cope with this level of uncertainty? It’s an approach that I have learned from “The Game Theory.” In-game theory, there are Finite and Infinite Games. I described the whole concept along with a strategy matrix in my article “Understanding The Games We Play – Strategic Mindset.” In a nutshell, Iranians who wait for the sanctions to be lifted are like Finite players who are playing an Infinite game.

In a nutshell, Iranians who wait for the sanctions to be lifted are like Finite players who are playing an Infinite game. They are waiting for something to change while the game continues with politicians announcing date after date. It likes a hamster wheel. If the hamster knows that it’s a wheel, he uses it as a treadmill. Otherwise, he always runs to reach the end, where there is no end.

Embracing The Unknown at The HUS Institute

The reason I described my unexplored areas is to set an example of how uncertain can situations can be, and also for the readers to understand that the optimum reaction to an unknown phenomenon is not always avoided it or even analyze it. It’s sometimes about embracing it.

Every single decision we make changes us both individually and collectively. And unknown areas, like at the edge of what we can analyze and what we can’t is the place for our minds to find creativity and opportunity. These are the places that innovation can change a lot of things and can have great rewards.